Available amazon.com, harpercollins.com, easons.com 23.99 euros

Tim Pat Coogan, in his new book, The GAA and the War of Independence, succeeds in creating the ‘intimate’ connection between the GAA and Irish Freedom. An anecdotal, conversational tone guides the reader from the founding of the association through the role of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, the effects of the revolutionary period (1912-23), the Northern Troubles and the GAA’s effort to tell Irish history by naming stadia after those who gave us our Irish freedom.

On the first of November 1884, in the billiard room of the Hayes Hotel in Thurles, Co. Tipperary, the founding members, about seven and almost all Fenians, saw this organisation as promoting Irish identity, reviving traditional games and facilitating Irish sentiment. Mayo athlete Patrick Nally and Clare teacher Michael Cusack were walking in Phoenix Park and saw no-one playing games, a symbol of the inertia of the time. Archbishop Croke related how the worst thing he had to endure was the sight of young men sitting around ditches with humps on them and no work to do. Due to the colonial system everything was English. Students were taught to be happy English children. English games were supported by the landlords. Suddenly the infant GAA ‘spread like the prairie fire’. Coogan details how British authorities in Dublin Castle were aware of the organization’s potential as a revolutionary seedbed and they treated the GAA from the outset as a semi-subversive movement.

An interesting anecdote is told of the author’s meeting in 1883 with one of South Korea’s senior advisers who displayed a ‘remarkable knowledge of Irish culture and history’. He told Pat that before the Japanese annexation of the Korean peninsula in 1910, they sent four professors to research the best method for colonizing a people. They were impressed by Britain’s record in Ireland, its systematic removal ‘of native culture, language, pastimes and dress’. The British had ‘incubated in Ireland feelings of inferiority’. ‘The initial growth of GAA clubs in the United States, for example, was fuelled by mass emigration that accompanied the trauma of the Great Famine in Ireland and its poverty stricken aftermath.’

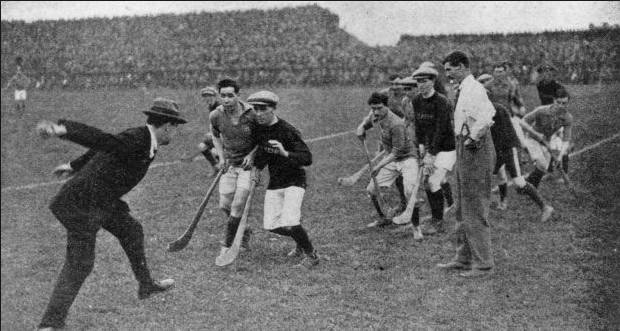

But while the Anglo- Irish Duke of Wellington claimed the battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton, Coogan puts forward a convincing case that Ireland’s War of Independence ‘in the early part of the twentieth century was won on the playing fields of the GAA’. ‘They thought if they got the men together and trained them in hurling, it would be a sort of martial art’. So the Irish Volunteers drilled with hurley sticks. Indeed Pearse’s famous oration at the graveside of O’Donovan Rossa in Glasnevin Cemetery was spoken surrounded by GAA members holding hurley sticks instead of rifles.

Coogan proclaims the GAA to be a multi-faceted organization, fostering a benign consciousness of being Irish which makes the movement a serious contender for the title ‘Most Valuable Institution in the Country’. Its reach is global. In 2017 a successful Asia Games was staged in Singapore. It has fostered the ideal of voluntarism and has contributed a distinctive sense of national identity that would be hard to replicate anywhere in the world.

The GAA is a broad organization. Thomas McCarthy, a founding member, played rugby for Ireland and worked as a District Inspector in the RIC. The Thomas McCarthy Cup, part of the peace process in Northern Ireland, is awarded for the annual competition held between the Republic’s An Garda Síochána and the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI). This evolving GAA was confident in its own identity to assist the Irish Rugby Football Union (IRFU) by leasing the Croke Park for Six Nations and other games. Peter McKenna accompanied Coogan, together with a set of architectural plans, into an investigation into the rumour that Girvan Dempsey’s try was on the spot where the Tipp player Michael Hogan was murdered on the afternoon of ‘Bloody Sunday – 21st November 1920. Earlier that day Michael Collins’s hit squad had struck a ‘body blow in a series of raids against a British military undercover death squad that had been making steady inroads into Collins’s Irish intelligence network’. It mattered that The GAA had decided to welcome rugby to Croke Park.

This fascinating book showcases the proud history of the GAA and its efforts to nurture the best of Irish identity. It is a must read for every GAA fan and enthusiast, at home and abroad.

Reviewed by Marcus Howard

Youtube: Easter Rising Stories

Facebook: Easter Rising Stories